Trees From Space: A New Early Warning System for Volcanic Eruptions

When Chile’s Chaitén Volcano erupted in May 2008—its first eruption in 9,000 years—scientists began exploring new ways to spot such volcanic unrest earlier. Now, thanks to a NASA-Smithsonian collaboration, trees near volcanoes might provide vital early warning signals—and we can monitor them from space.

How Trees Warn of Volcanic Activity

Rising magma beneath a volcano releases gases, including carbon dioxide, which trees absorb. This extra carbon dioxide often causes nearby vegetation to become greener and more vibrant—a subtle but detectable sign of volcanic activity.

Using satellite images from NASA’s Landsat 8 and airborne instruments from the Airborne Validation Unified Experiment: Land to Ocean (AVUELO), researchers are tracking these changes in vegetation from orbit and validating the data on the ground.

Carbon dioxide released by rising magma bubbles up and heats a pool of water in Costa Rica near the Rincón de LaVieja volcano. Increases in volcanic gases could be a sign that a volcano is becoming more active. Credit: Alessandra Baltodano/Chapman University

Why Early Warning Matters

About 10% of the world’s population lives near volcanoes, facing dangers such as flying debris, ash clouds, and toxic gases. Volcanic eruptions can also trigger mudslides, tsunamis, and widespread ashfall far beyond the eruption site.

Since eruptions can’t be prevented, spotting early signs—like increased volcanic gases—is critical for timely evacuations and safety measures. While sulfur dioxide is easier to detect from space, carbon dioxide is released earlier but is harder to measure directly.

Gregory Goldsmith from Chapman University launches a slingshot into the forest canopy to install a carbon dioxide sensor in the canopy of a Costa Rican rainforest near the Rincón de LaVieja volcano. Credit: Alessandra Baltodano/Chapman University

Vegetation as a Proxy for Volcanic Carbon Dioxide

Detecting volcanic carbon dioxide through vegetation changes adds an important tool alongside seismic activity and ground deformation to understand volcanic unrest.

Volcanologist Florian Schwandner of NASA Ames Research Center explains the goal: “We want to improve and advance volcano early warning systems.”

Alexandria Pivovaroff of Occidental College measures photosynthesis in leaves extracted from trees exposed to elevated levels of carbon dioxide near a volcano in Costa Rica. Credit: Alessandra Baltodano/Chapman University

The Challenge of Measuring Volcanic Carbon Dioxide

Volcanoes emit significant carbon dioxide, but it’s often masked by the background atmospheric levels, making direct satellite detection difficult. Field measurements require scientists to visit often remote and dangerous volcano locations, which can be costly and risky.

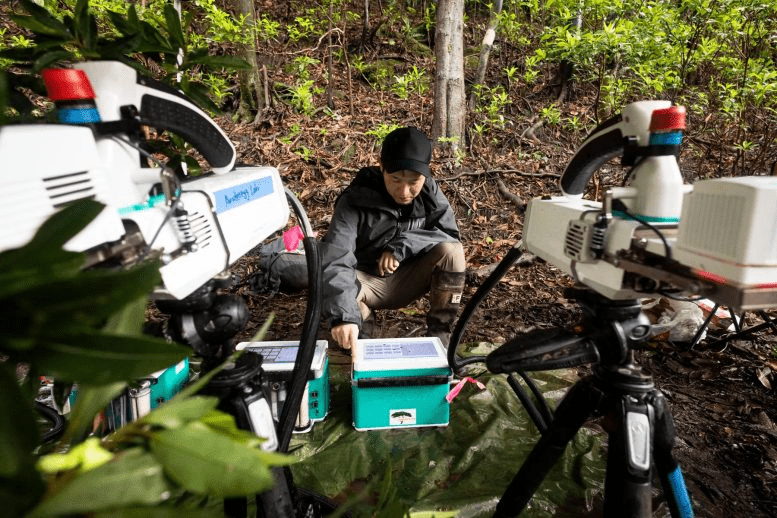

Chapman University visiting professor Gaku Yokoyama checks on the leaf-measuring instrumentation at a field site near the Rincón de LaVieja volcano. Credit: Alessandra Baltodano/Chapman University

Scientists Track Tree Responses Instead

To bypass these challenges, volcanologists, botanists, and climate scientists collaborate to monitor tree health and leaf color as an indirect measure of volcanic gas emissions.

Nicole Guinn from the University of Houston, for example, used satellite imagery from Landsat 8, NASA’s Terra, and ESA’s Sentinel-2 to study trees near Italy’s Mount Etna, confirming a strong link between tree greening and magma-released carbon dioxide.

Ground Verification Through Airborne Missions

In March 2025, NASA and Smithsonian researchers flew spectrometers over Panama and Costa Rica to measure plant coloration, complementing leaf samples and carbon dioxide readings collected near Costa Rica’s Rincon de la Vieja volcano.

“This research connects ecology with volcanology,” says Josh Fisher from Chapman University. “It not only helps us detect eruptions but also reveals how trees respond to increased carbon dioxide in the environment.”

Limitations of Tree-Based Monitoring

Not all volcanoes have sufficient tree cover to use this method effectively. Environmental factors such as fires, weather, and plant diseases can complicate data interpretation. Additionally, different forest types respond variably to carbon dioxide changes.

A Real-World Success Story

Schwandner’s team installed carbon dioxide sensors at Mayon volcano in the Philippines. In December 2017, the system helped detect early signs of eruption, leading to a successful evacuation of over 56,000 people before a major eruption in January 2018—resulting in no casualties.

A Promising New Tool for Volcano Monitoring

While no single method can provide all answers, monitoring vegetation changes from space offers a valuable new piece of the puzzle. Schwandner sums it up: “Tracking volcanic carbon dioxide’s effect on trees won’t be a silver bullet—but it could be a game changer.”